26 Feb The Big Question for the U.S. Economy: How Much Room Is There to Grow?

The U.S. economy will enjoy a mild cyclical rebound in 2017, then return to a lower growth rate more in line with long-term potential. Gross domestic production, inflation-adjusted, grew at fairly tepid rates over the past three quarters. But jobs are increasing at a moderately good pace, with unemThe financial district in downtown Manhattan has been thriving. Buildings like Brookfield place have filled vacant office space, and starting salaries have risen.

The most important issue for the United States economy in 2017 and beyond is whether it’s near its speed limit.

It has taken eight years of glacial expansion, but the nation is closing in on what economists believe to be its full productive capacity. It’s nearing that level of activity in which nearly everybody who wants a job has one, and factories and offices are cranking at full speed.

If the economy grows just 2.5 percent this year, gross domestic product will reach the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of the nation’s economic potential by the end of the year. If the Trump administration succeeds at achieving the 4 percent growth the president has said he seeks, we’ll be there by the Fourth of July.

If there is in fact more room to grow beyond the budget office’s estimate of “potential G.D.P.,” an economic boom remains possible. If there isn’t, higher growth will translate into inflation, not higher output and incomes. The question for the Trump administration, the Federal Reserve and every American who wants a higher paycheck is how much slack there really is in the economy.

Economic slack takes the form of empty warehouses and office parks; of machines that run eight hours a day when they were built to run for 12; and, most important, of millions of Americans who might be coaxed to work in a booming economy but who aren’t even looking for a job now.

If there is a lot of slack, then the Trump administration’s ambitious growth targets look more plausible, and the Fed should move slowly on raising interest rates so as not to choke off the expansion just as it’s getting going. If there’s not very much — if this is about the best the nation can expect to do — then either the Fed will raise rates more quickly to choke off growth or inflation will burst higher, or both.

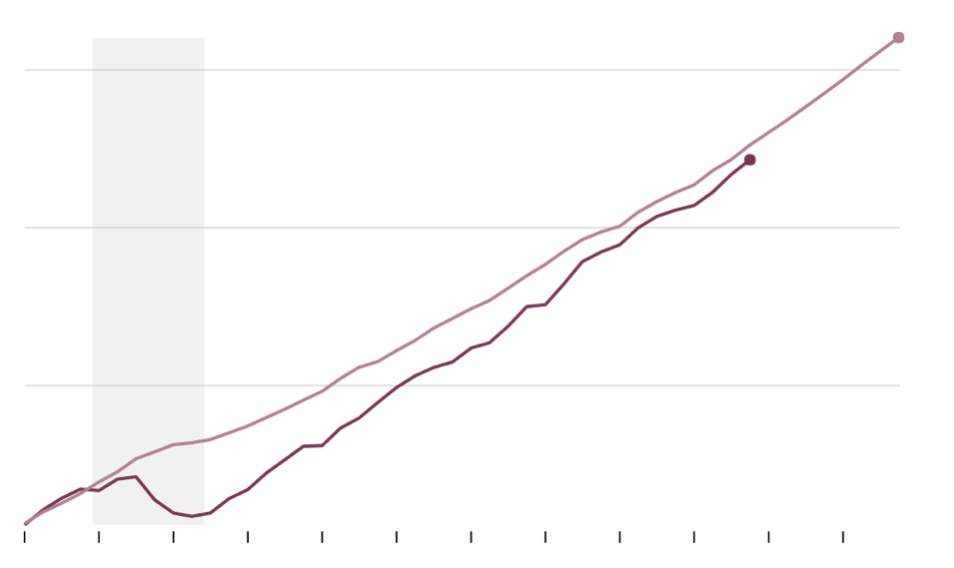

Shaded area indicates recession

Sources: Congressional Budget Office; Bureau of Economic Analysis

In assessing how close we are (or aren’t) to full capacity, it helps to look at America’s industrial parks and office complexes. The Federal Reserve watches the industrial sector by measuring what is called factory capacity utilization. American companies were operating factories at 75.7 percent of their potential in January. That’s roughly the rate they’ve been at for the last five years.

Experience suggests it could go higher. In the spring of 2007, the rate was 79.5 percent. It was above 80 percent for the better part of the 1990s.

In other words, the manufacturing sector would seem to have room to produce more stuff even without expanding factory floors or adding equipment. At Caterpillar, the giant maker of heavy equipment based in Peoria, Ill., Jim Umpleby, the chief executive, told analysts last month that, even as it closely managed costs, “we’re also preserving capacity for a potential increase in business whenever that comes.”

Economic slack is trickier to measure in the service sector; good luck judging whether, say, an insurance company is operating below or at its full potential. But one window into it is the office vacancy rate.

Nationwide, 15.8 percent of office space was vacant in the final months of 2016, according to the real estate information firm Reis. That was down from a recent high of 17.6 percent in 2011 — but could still have room to fall. In the last expansion, it fell as low as 12.5 percent, implying that millions of square feet of offices are sitting idle, ready for white-collar workers to fill them.

“Vacancy has fallen, but there are still some large blocks of space out there,” said John Ferguson, president of the Southeast division of the commercial real estate firm CBRE. “A tenant can typically find a short-term solution if they need to, even if it’s not perfect for the long term.”

Astronomers can’t observe a black hole directly; they can determine where one is only by measuring how it affects nearby matter. Potential output is similar. For all the apparent precision of reports from government agencies, potential G.D.P. isn’t something that can be directly measured. It’s a judgment based on other evidence.

How big is the population of prime working-age people, and how many of them would be expected to seek work? How low in the past has unemployment gone before inflation became a problem? What is the recent record of productivity growth?

No Comments