Stocks are risky investments; they go up and they go down. Some investors view rallies as time to sell and down days as opportunities to buy. Others take the opposite views.

KYUR philosophy is, what matters is the amounts of wealth you end up having for education, buying your dream home, retirement, or preservation of your life styles.

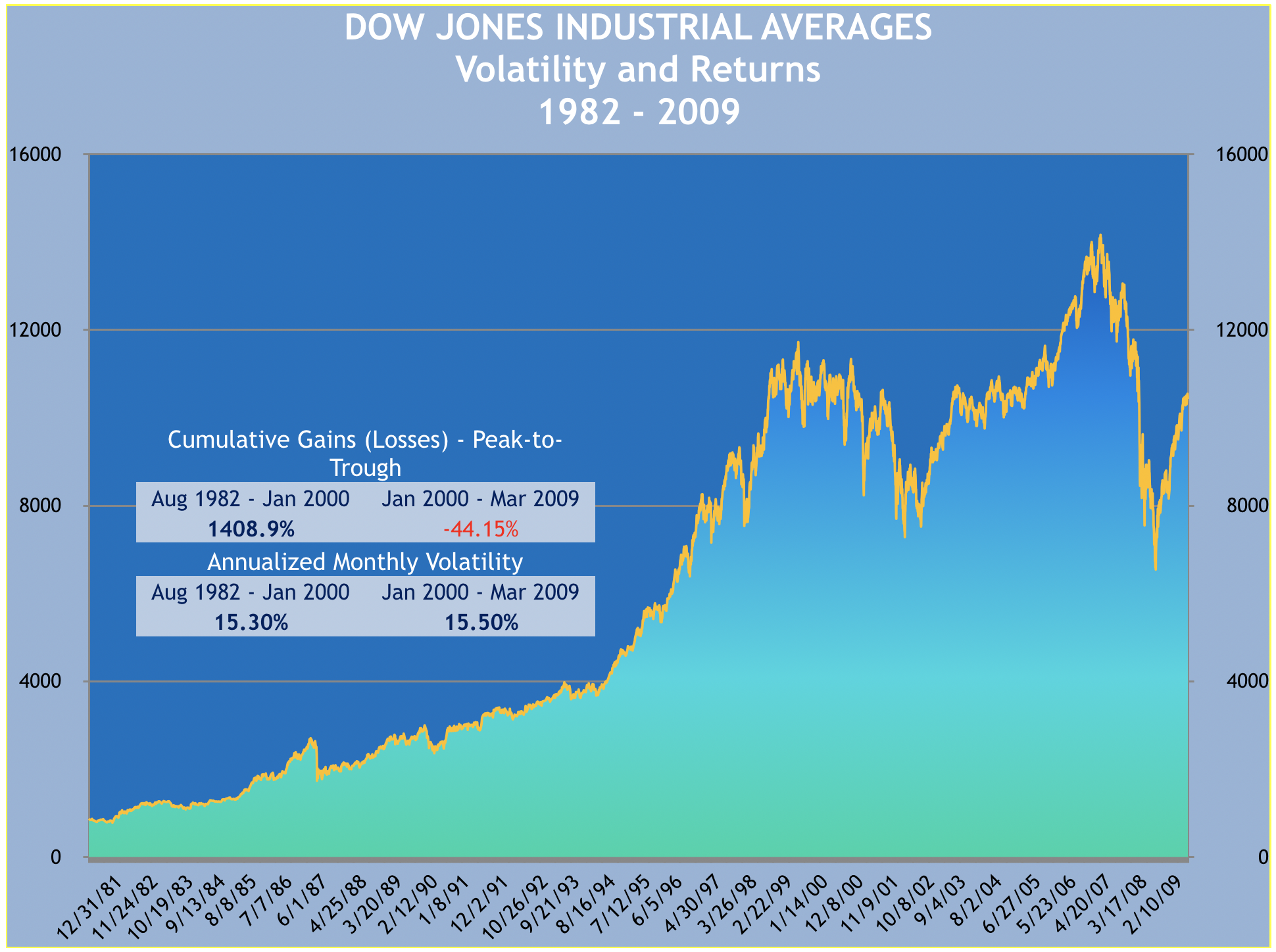

Do you know that during the period between August 1982 and December 1999, the Dow Jones Industrial Average generated total gains of 1,409 percent – 14 times of your investments?

In comparison, between January 2000 and February 2009, if you had invested in the Dow, you would have lost -44 percent, almost half of your capital? One would think the bear market of 2000 to 2009 was far riskier than the almost two-decade long bull market of 1982 to 1999 –as graphically shown nearby.

But if one uses volatility to measure risks as in Mean Variance Optimization, the two periods would be deemed equally risky. Both periods have the same annualized monthly volatility of 15.2 percent. For explanations of volatility as the measure of risk in Modern Portfolio Theory, see writings by the father of MPT and Nobel Laureate Harry M. Markowitz , “Portfolio Selection,” The Journal of Finance, March 1952, and his Portfolio Selection: Efficient Diversification of Investments, John Wiley & Sons, (reprinted by Yale University Press, 1970.)